Los Angeles is more than Hollywood stars. From hikes with killer views to beaches straight out of a rom-com, here are 10 must-do LA experiences for Filipino travellers or any wanderers in general!

How Travelling Made Me A Proud Morena

“I love your tan!” — a compliment I’ve been receiving since I started surfing regularly. But years ago, it was a totally different story.

I’m a water baby. I know this because there’s this photo of me as a one-year-old in the middle of a pool. My dad told me once that he threw me into the pool to teach me how to swim — “because that’s how the Egyptians do it.” My mother was less enthusiastic about the idea, but tolerated my father anyway. They enrolled me in a swimming school when I was six.

Although I couldn’t claim to be the greatest swimmer in the world, I’ve been in love with the water since then. I memorised every Little Mermaid song, danced to Here on the Land and Sea, and wore a mermaid tail whenever I had an excuse to do so. I’d run around with shells on my chest even before breasts grew out of them. I even had singing lessons and tried growing out my hair, because that’s what mermaids do.

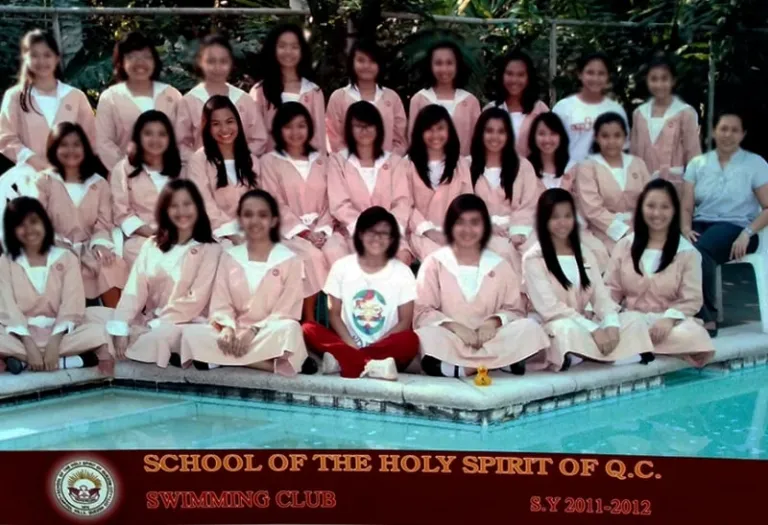

SHSQC Swimming Club (2012)

SHSQC Swimming Club (2012)In high school, I became a competitive swimmer. I also became the darkest girl in class. Coming from an exclusive all-girls school, I didn’t have a problem with my colour back then. Most of my classmates were strong and confident young ladies and it wasn’t usual among us to seek approval for our looks. Generally, we were more focused on building friendships, developing leadership skills, and striving for better grades. Yes, the popular girls were mostly mestizas, but I wasn’t too affected by that since it wasn’t really a big deal.

On social norms and happiness

Indonesia (2016) | Image credit: Cris Uy

Indonesia (2016) | Image credit: Cris UyAs I grew up feeling confident in my own skin, I’m more sure that insecurities aren’t innate. No baby comes out feeling ugly in his or her colour. We only develop self-doubt through years of rejection (i.e. “Maganda ka sana kung maputi ka.”), bullying (i.e. “Mukha kang unggoy!”), and comparison (i.e. “Ang puti ng ate mo, bakit ikaw ganyan?”)

My insecurities came out when I went to university, where I was exposed to different people from diverse backgrounds. There, I heard people calling dark-skinned girls “manang.” Some were even implying that those with darker skin looked dirty and poor. My guy friends would crush on fair-skinned girls exclusively. And, since we were in a state university, it wasn’t so much a big deal if a girl was smart. She’d only be worthy of special attention if she were pretty — as in, light-skinned.

For the first time in my life, I wanted to be whiter. And it wasn’t hard at all. In the Philippines, almost every bath and beauty product claim to have “whitening effects.” Basically, all that was left for me to do was to stay out of the sun.

Naturally, I got whiter. But was I happier? Weirdly enough, I wasn’t. In fact, I felt even more insecure. Each time I looked in the mirror, I saw my every single imperfection. As a result, I underwent facials I didn’t afford, sacrificing my savings while at it. I wore foundation everyday. Contour to make my nose look smaller. Mascara to make my eyelashes seem longer. These would’ve been okay, if only I enjoyed putting on makeup. But I didn’t. Still, I did all these because in my mind, this was my only way to please society.

The colour of happy

Baler (2018) | Image credit: Kenn Angala

Baler (2018) | Image credit: Kenn AngalaSince my obsession with looking whiter, it’s been a long and tough journey towards self-love. There have been days too toxic that I’ve needed to spend time off from social media. I’ve tried reading and writing instead, instead of living on Instagram and Netflix — the world of perfect-looking women. Still, even while being disconnected, I was surrounded by people who were overly-focused on looks. I really couldn’t blame them, since the city has become so commercially-saturated.

So, I decided I needed a new environment. I travelled to the beach and spent a couple of months there.

As a water baby, it was inevitable for me to fall in love with the ocean. But when I learned how to surf, I was even more addicted to the call of the sea. So much that I’d practically forgotten about my looks. I remember not recognising myself when I looked in the mirror for the first time in two weeks.

Also read: I Spent Two Months at the Beach to Cure a Broken Heart & Here’s What I Learned

Even as I say this, I must admit that self-acceptance didn’t come easy. For the first few days I was in Baler, I wore sunblock religiously (without even bothering to know if it was a reef-safe brand — boo!) After every surf session, I’d put on whitening cream on my face. But later on, I realised my efforts were useless. I’d spend at least a couple of hours surfing everyday, and I didn’t want to stop surfing just to keep my fair skin. So, I decided to take in the sun. And it was liberating.

A traveller’s badge of honour

Vietnam (2018) | Image credit: Samuel Uy

Vietnam (2018) | Image credit: Samuel UyAfter Baler, I began travelling more. I’ve become more exposed to several stunning people from different ethnicities, and I’ve realised how beauty comes in all shapes and colours.

Furthermore, trekking the world with fellow jet setters, I wore my skin like a badge of honour. It made me feel confident, like I was exuding an aura of adventure just because of my tan. No longer did I have to hide from the sun. I relished under it instead. Now, I could happily spend hours walking and swimming without worrying about getting darker.

But more than my personal happiness and sense of freedom, I hope that the stigma on morenas will ultimately change. I’m happy that the world is embracing diversity nowadays, but we still have a long way to go.

Also read: Changes I Embraced That Made Eyebrows Raise When I Started Travelling

For example, my grandmother commented on my tan the first time she saw me after I’ve been travelling — “Mukha kang foreigner! Ang ganda!” I took it as a compliment, of course, but I hope she’d said that I looked like a Filipino. A morena, at that. I am one, after all.

Published at

About Author

Danielle Uy

Subscribe our Newsletter

Get our weekly tips and travel news!

Recommended Articles

10 Best Things to Do in Los Angeles 10 Commandments for Responsible Travel Flexing Spread the good word!

10 Cutest Cafes in Japan That Are Totally One of a Kind From Pikachu snacks to Totoro cream puffs, here are 10 themed cafes in Japan that prove café hopping should be part of your travel itinerary.

10-day Christmas and New Year Japan Trip: Complete Travel Itinerary Celebrate Christmas and New Year in Japan with this 10-day holiday vacation itinerary packed with Tokyo lights, Kyoto charm, and Osaka adventures.

10 Fairytale Castles In Europe Filipinos Need To See! Permission to feel like royalty even for a day?!

Latest Articles

Japan Cancels Famous Cherry Blossom Festival Due to Overtourism Why the festival stopped

You Can Now Visit Kalayaan Islands a.k.a. West Philippine Sea for ₱30,000! Kalayaan is officially open for "patriotic tourism," but it’s definitely not for the weak!

Valentine’s Date Guide to the National Museum in Manila A quiet romantic date

China Bans Filipinos From Entering Hong Kong And Macau See if your travel plans are at risk!

Philippines Is First In Southeast Asia To Launch Satellite-To-Phone Technology You can now text and call from dead zones as Philippines launches satellite-to-phone tech